Editor’s Note:

This is the inauguration of what Monrovia Weekly hopes is the beginning of a beautiful friendship and collaboration with one of the foremost historians of Monrovia’s colorful history, Mr. Steve Baker.

Baker is also well known in the city, not only for his tenacity for the obscure details in history, but also his dry sense of humor and unparalleled ability to manage the city’s treasury.

Alta Vista, baby!

By Steve Baker

Monrovia Historian

Jerome Increase Case was born Dec. 11, 1819 in Oswego County, N.Y. As a young man, he tinkered with a primitive threshing device purchased by his father, made improvements, and then perfected his own threshing machine by the early 1840s. He ultimately located in Racine, Wis., where he built a large manufacturing plant. In the 1860s he was joined by several partners and the J. I. Case Company was organized. It evolved into a prosperous farm implement manufacturer that exists today as the Case Company, and some of the company’s vintage tractors are highly sought collector’s items.

In the 1870s, with greater wealth and fewer responsibilities, Case turned his attention to the sport of kings—horse racing. Case spent considerable time breeding racehorses on his Hickory Grove Farm near Racine. One of Case’s favorites was a black gelding, foaled in 1878, that was given the name Jay-Eye-See, a phonetic rendering of Case’s initials. Jay-Eye-See set a trotting record in 1882 and won many other races, becoming the Silky Sullivan of his era.

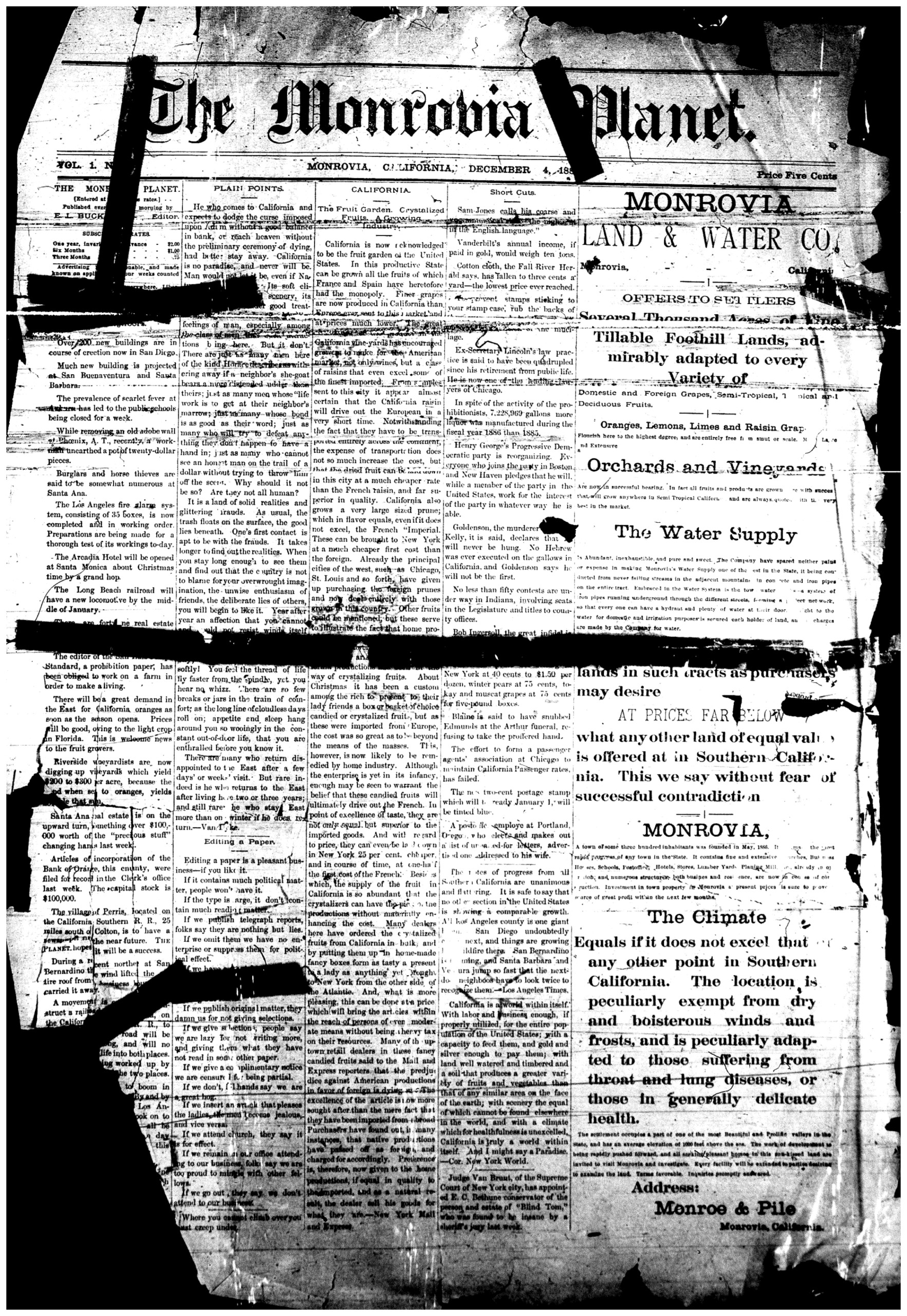

In the meantime, Case had discovered the fledgling community of Monrovia, Calif., nestled at the base of the San Gabriel Mountains. Case was nearing 70 and the harsh winters of Racine were an inducement to establish a winter residence in sunny Southern California. The “Monrovia Planet” (Planet) of March 26, 1887 proudly claimed that J. I. Case of Racine, Wis. and J.M. Studebaker of South Bend, Ind. were new residents of Monrovia and “have invested about $200,000 in Monrovia real estate, and will both erect handsome residences in the near future, as soon as plans, etc. can be prepared.”

Case was also one of the founders of the Granite Bank of Monrovia, serving as vice president of the institution. His winter home, completed in 1887 at a value of $10,000 in 1887 dollars, still proudly stands in the foothills of Monrovia.

A week earlier, the Planet had reported “that famous horse, J.I.C. [sic] has been purchased from Mr. Case and will be brought to Monrovia.” Either the Planet source was inaccurate or there was a change of heart, since Jay-Eye-See never did venture south of the Tehachapi Mountains. But his name did. William Monroe—who bought land from E.J. “Lucky” Baldwin in 1884, settled the future site of Monrovia, and gave his name to the new community in 1886—decided to name one of the streets in his 1887 Monroe Addition to the Monrovia Tract after the famous race horse. Rather than using the phonetic rendering Jay-Eye-See, Monroe chose to use J.I.C. instead. The uninitiated thought the street was named for Jerome I. Case, but it was actually named for his horse.

Speaking of Jay-Eye-See, he was injured in 1889 and was retired from racing, but not before he became nationally famous and was even featured in prints by Currier and Ives. Much lesser known is the fact that Jay-Eye-See captured the attention of a noted phrenologist of the time, who published a book on phrenology with an image of the horse on the cover. I know, because lurking somewhere in my collection of historical memorabilia is that very book.

The last reference to Jerome I. Case in Monrovia comes from the “Monrovia Messenger” of Feb. 19, 1891, “J.I. Case of Racine, Wis., is in Monrovia at present. He owns considerable ranch property and has a beautiful home here.” It was his last visit. He died Dec. 22, 1891 in Racine at the age of 72.

But what of Jay-Eye-See? After his injury in 1889, he was re-trained to a new gait, joined the race track once again, and set a pacing record in 1892. He died in 1909 at the ripe old age of 31 and was buried on the Hickory Grove Farm. When his unidentified resting place was threatened by development, aficionados located his bones and removed them to a safe storage area. As funds permit, they will be re-interred in a memorial near the Case family mausoleum in Mound Cemetery.

The City of Racine also memorialized Jay-Eye-See by naming one of their streets after the famous race horse—and unlike Monrovia, they used the proper spelling. The street exists today. Monrovia, on the other hand, succumbed to the urge to change the prosaic “J.I.C.” to “Alta Vista” in the early years of the last century when Spanish place names were coming into vogue. It is fitting yet ironic that the original name of the street succumbed at about the same time that the horse whom it honored succumbed as well. Old maps of Monrovia kindle the memory and old historians love to tell the tale.