By Susie Ling and Roy Nakano

The movie “Green Book” recently won a Golden Globe for Best Motion Picture. The real “Green Book,” however, was a project of Victor H. Green, a postal worker in Harlem. Like Martin Luther King did years later, Victor Green pursued a dream, but for the travelling African-American motorists.

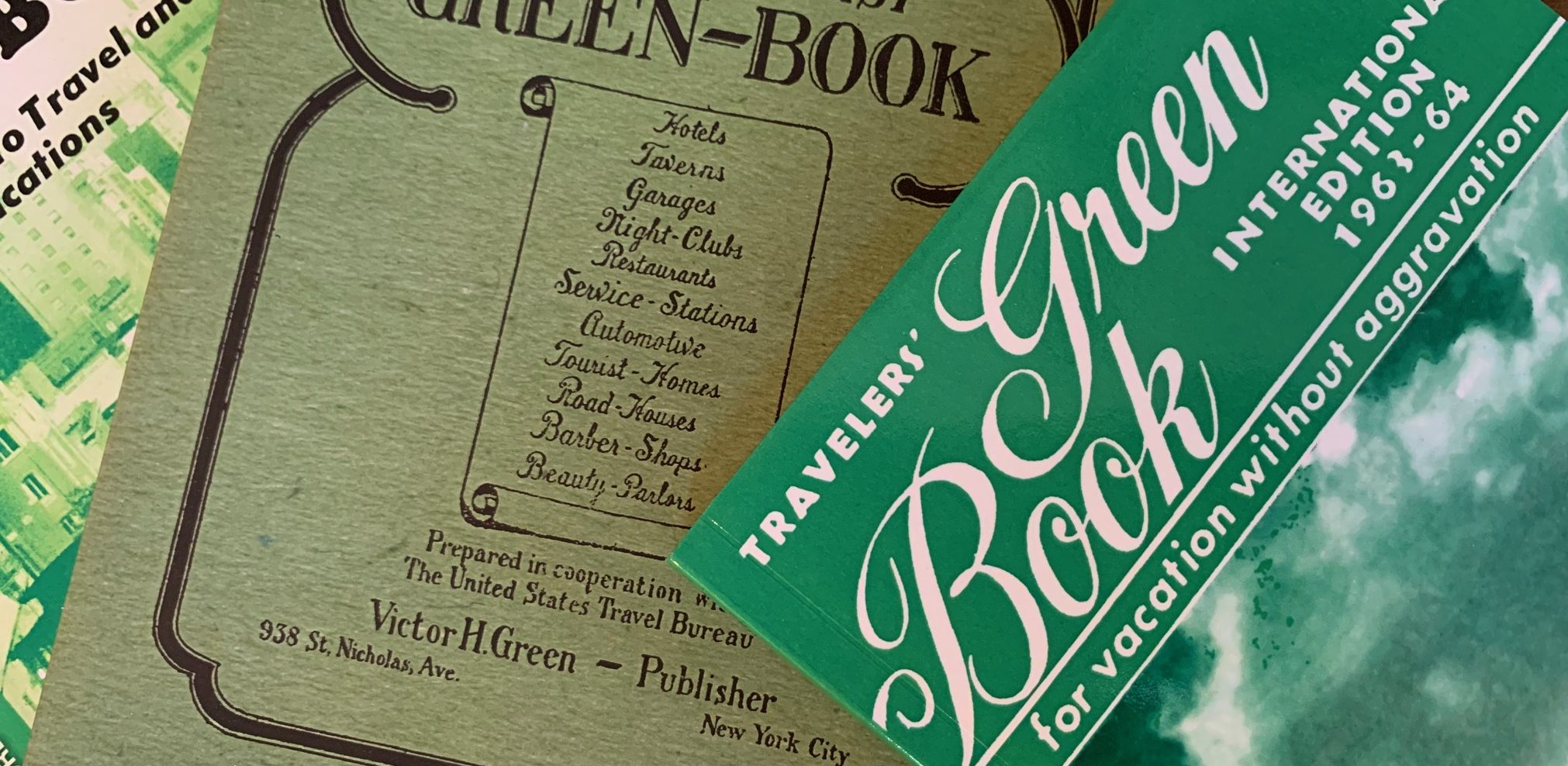

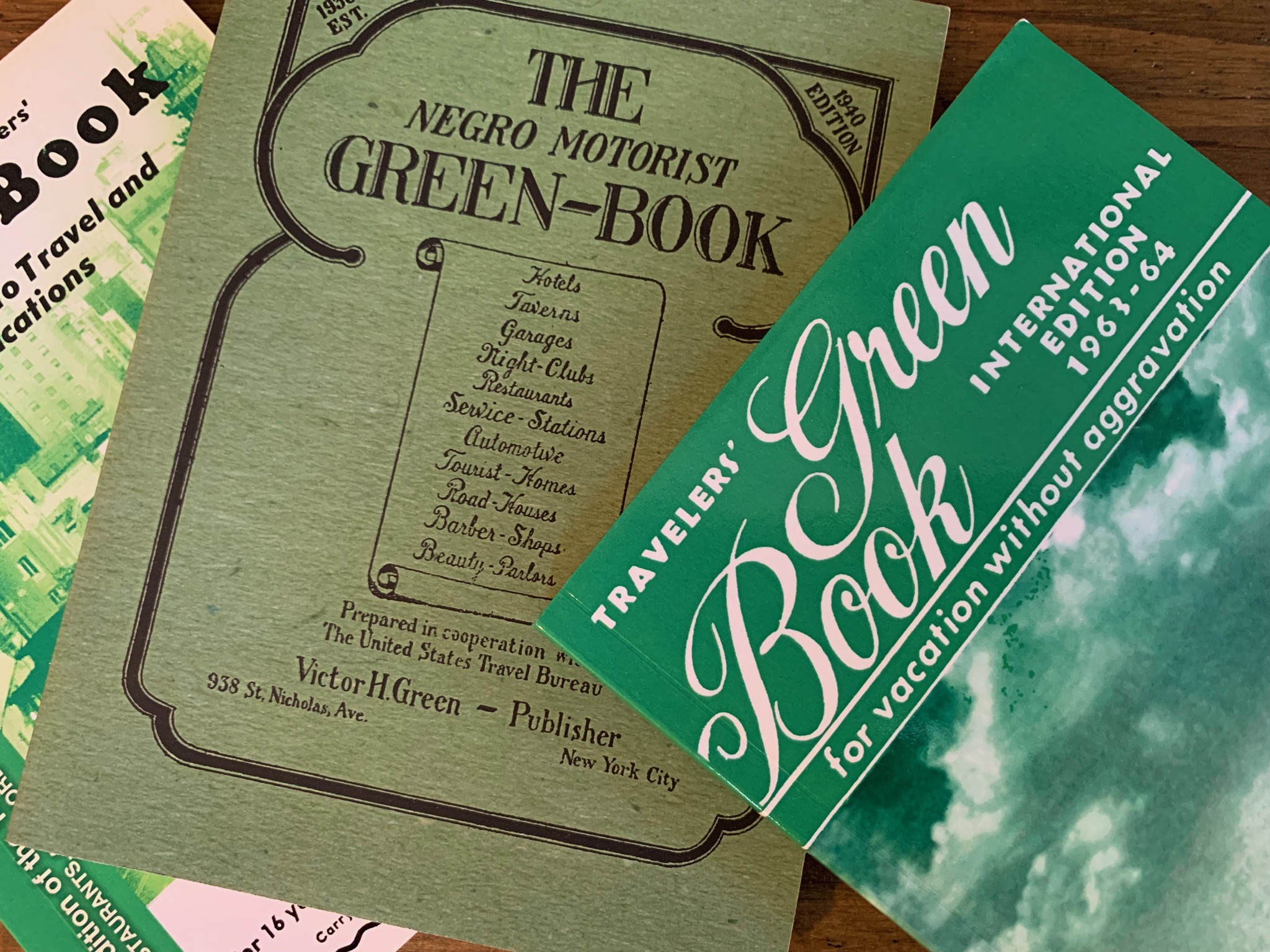

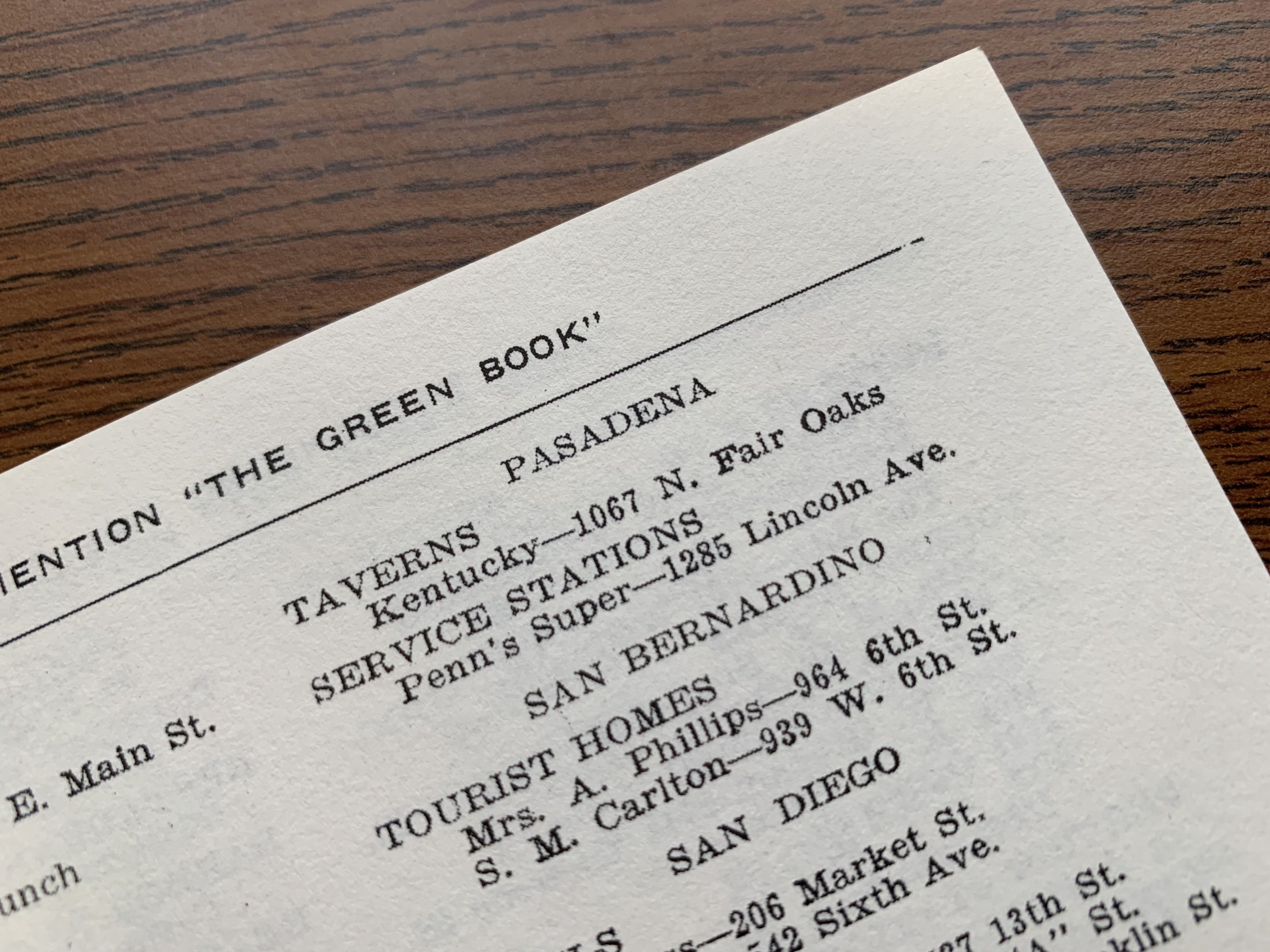

The first “Green Book” in 1936 listed service stations, restaurants, lodging, and barber shops in New York that would welcome an African-American clientele. This was a great service for newcomers to the city in an era when racial segregation was common across the nation. Mr. Green expanded his listings yearly.

He explains in the 25-cent 1940 “The Negro Motorist Green Book,” ”The white traveler for years has had no difficulty in getting accommodations, but with the Negro it has been different. Before the advent of Negro Travel Guides, he has had to depend on word of mouth and then sometimes accommodations weren’t available.” By the 1963-64 edition, the title evolved to “The Travelers’ Green Book, for vacation without aggravation.”

Perhaps after Dr. Martin Luther King’s 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, the nation had turned a page and the need for “The Green Book” lessened. The last edition was published in 1966, two years after the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

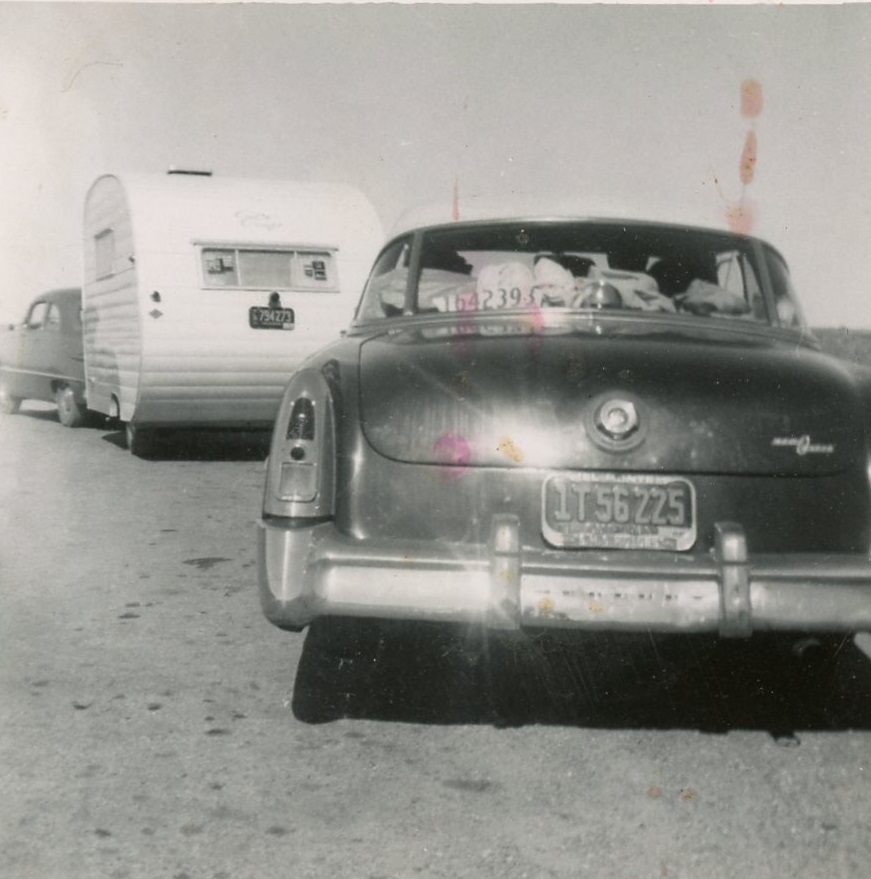

Ninety-one-year young Jessica Valentine of Pasadena remembers her trip from the Jim Crow South to California in 1936. Her mom, dad, and a friend who would help with the driving, sat in the front of their Oldsmobile. In the back seat were her aunt and four children. Valentine said, “We took turns sleeping on the floor. After the home-prepared food was consumed, we had to look for food stands to purchase food. Some of the restaurants would permit take-out service when Daddy went to the back door. We were disappointed and surprised that the treatment of Negroes was not much different, even after we left the Deep South.”

Valentine can’t remember where they used accommodations but she said, “I can say without any reservations that no unpleasant incidents were allowed to dampen the enjoyment of our journey.” Valentine attended segregated Huntington Elementary, went on to college at a HBCU (Historically Black College and University), and became a LAUSD school teacher. When she was a little girl n Mississippi, she was picking cotton.

Monrovia Councilmember Larry Spicer was born in California, but as his folks both came from the South, the family often traveled there to visit family. He said, “When we were younger, we often went back to Mississippi. On the trip, we would see the prejudice. At some gas stations, we couldn’t get out. My mother would prepare food for the whole trip. Back in those days, my dad would drive straight through on Route 66’s two-lane highways. We would always caravan with the Barnes family, who lived next door to us in Monrovia. When we got to Mississippi, they would go to the right and we would go to the left. Our people lived by the Delta.”

Richard Markham graduated from Duarte High School in 1968. He said, “One time, in 1959, our family drove down to Mississippi and Florida. I was nine. It was quite an experience. I remember seeing this big glowing fire at a distance; it was a cross burning by the KKK. I saw all these people hanging around. I asked my dad and he said, ‘I’ll tell you about that one day.’ He never told me. But I remember. I also remember certain establishments where we had to go to the back door. We couldn’t get a hotel room so we would sleep in the car. I’m a California guy so it was all strange. We saw different restrooms and drinking fountains. It was somewhat frightening.” Richard graduated from UC Riverside and retired from law enforcement.

Victor Green Has the Last Laugh

Green vowed to keep printing the guide until the laws of the USA would make it needed no longer. In the introduction to his 1949 edition, Green wrote: “There will be a day sometime in the near future when this guide will not have to be published. That is when we as a race will have equal opportunities and privileges in the United States. It will be a great day for us to suspend this publication for then we can go wherever we please, and without embarrassment. But until that time comes we shall continue to publish this information for your convenience each year.”

It looks like Victor Green has the last laugh on the “Green Book:” 50 years after the last issue was published, it’s being published again—both in print (reproduced by another publisher and available on Amazon.com) and in the form of an acclaimed movie. This time, it’s so we don’t forget why the original was needed.