By Galen Patterson

Riyo Sato was a developing artist by the time she was detained in 1942. She was sent to Santa Anita Park, where she waited out a portion of the war in captivity before being transferred to Wyoming, to a different detention facility called “Heart Mountain.”

Cameras were confiscated within the detention camps. The reason why is the same reason that the Japanese/American population within the U.S. was detained to begin with: the war with Japan was on and the country wasn’t taking any chances.

While in captivity, Sato obtained onion skin paper and charcoal pencils and began sketching. She sketched scenes from the daily life inside Santa Anita Park’s internment camp, of things and people’s daily lives. “I think she just wanted to keep her skills sharp,” said Sato’s niece Pam Hashimoto. However, Sato didn’t talk about her time in Arcadia very often according to Hashimoto, so the precise reasons may never be known, but what Sato left behind is more than brief drawings of daily life in 1940s internment. Her sketches are part of the collective voice of the detainees.

After the war and Sato’s subsequent release, she moved east, taking a job doing sketch design for Curtiss-Wright in Buffalo, N.Y. She flew in airplanes and drew aerial sketches for the company, and eventually relocated to Chicago where she taught the children of the Chicago School District until June of 1984, when she retired. She spent her life traveling the world, collecting artifacts and curios from across the planet. Sato continued to reside in Chicago. It was in Chicago that the sketches were discovered.

Hashimoto was sorting through her aunt’s belongings after her funeral. Pam was one of Sato’s closer relatives, both geographically and emotionally, and thus found herself in Sato’s independent living facility apartment taking stock of the overwhelmingly diverse objects collected and displayed.

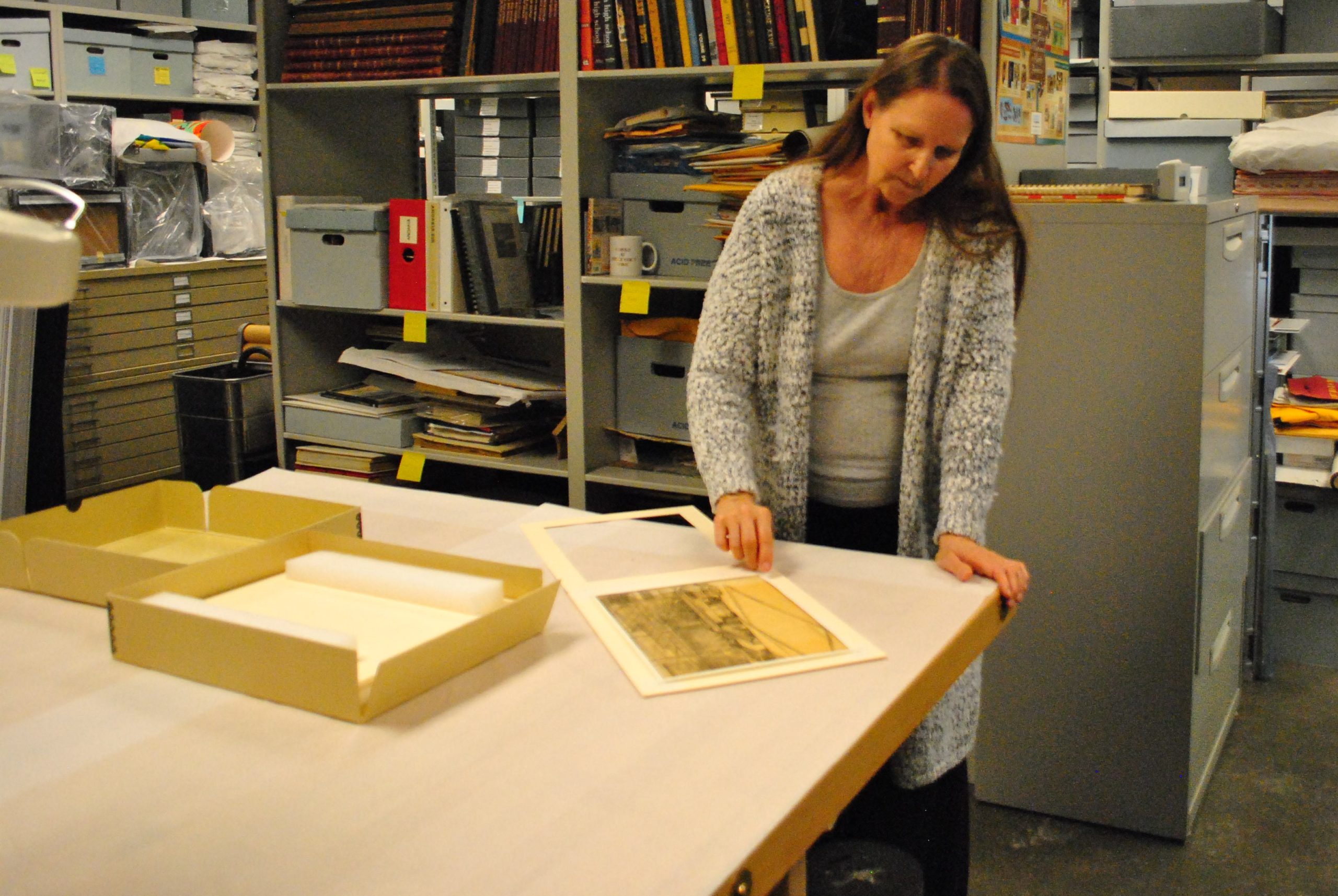

An old wooden crate laid unopened among the possession and when she opened it, “I was astonished,” says Hashimoto. Inside were the sketches of Santa Anita Park, preserved and possibly forgotten. “I think the crate was probably from her California days,” she says. Hashimoto doesn’t believe the sketches were ever meant to be displayed.

Once Hashimoto realized what she had stumbled upon, she set about finding and contacting a museum somewhere near Santa Anita. She thought: “They really should go somewhere near where it happened, so people can understand.” The sketches might mean more to the residents that don’t know about Santa Anita’s role in the detainment of Japanese-Americans, and for those who do know and are curious.

She contacted Dr. Dana Hicks at the Gilb Museum, across the street from the park. Hashimoto was impressed with Hicks’ devotion to preservation and the way she planned to display them.

Hicks and the Gilb staff have worked out a system by which they do not have to physically touch the actual surface of the sketches. The sketches held their own exhibit within the museum and when they are not all on display she rotates them out monthly so that the museum stays fresh and the sketches stay visible.

Sato spent her life creating art and inspiring those around her to appreciate it. She traveled extensively even in the later years of her life. “She went trekking in the Himalayas when she was in her 70s,” says Hashimoto.

The sketches are snapshots captured in the mind of a young girl captured by the top minds in a country at war. They show people working on making camouflage netting for the troops overseas and detainees staring longingly beyond fences. They are primary documents for those seeking to understand life inside the camps and they are a treasure to the City of Arcadia in that respect.

“Since I’ve given them to Arcadia, I’ve spoken to other people that say ‘why did you give them there?’ Or ‘we’d love to have them,’ but I’ve never second-guessed or regretted sending them there,” says Hashimoto.