By May S. Ruiz

French artist and astronomer Etienne Leopold Trouvelot (1827-1895) is largely unknown to most of us but it would be such a shame if his beautiful drawings didn’t get the acknowledgment and appreciation as the works of magnificence that they truly are.

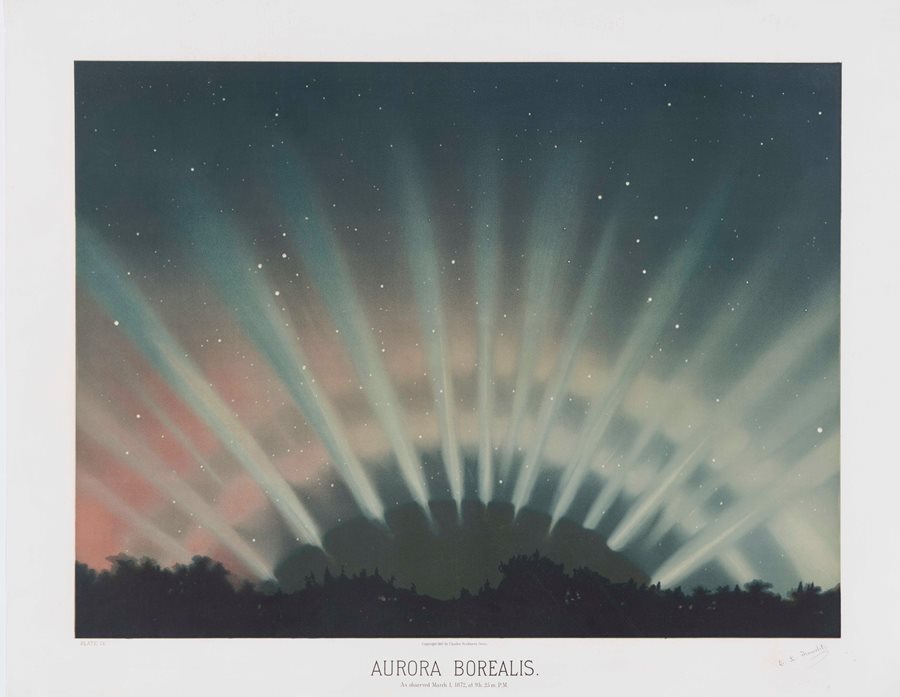

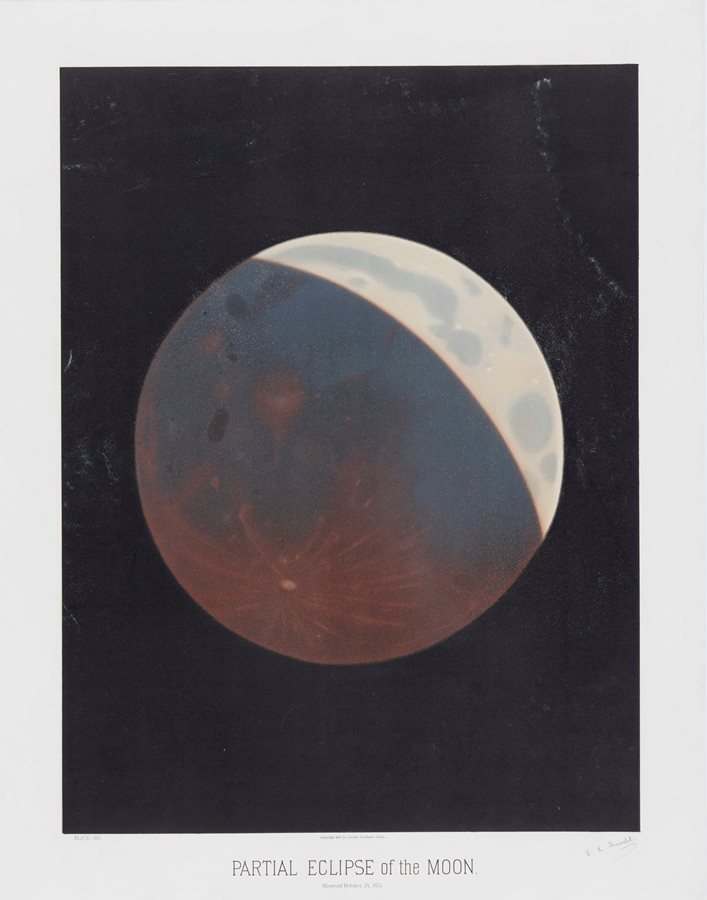

From April 28 through July 30, at the West Hall of The Huntington Library, we have the opportunity to view a rare set of lithographs depicting the pastel drawings of planets, comets, eclipses, and other celestial splendor that he created during his lifetime, in an exhibition aptly titled “Radiant Beauty: E.L. Trouvelot’s Astronomical Drawings.”

“The set of 15 chromolithographs was the crowning achievement of Trouvelot’s career,” declares Krystle Satrum, assistant curator of the Jay T. Last Collection at The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. “He was both an extraordinarily talented artist and a scientist, producing more than 7,000 astronomical illustrations and some 50 scientific articles during his working life. The high quality of the artwork and the scientific observation demonstrate his uncanny ability to combine art and science in such a way as to make substantial contributions to both fields.”

Trouvelot worked at the Harvard College Observatory where he made highly detailed drawings of his observations, many of which were published in the Annals of the Astronomical Observatory of Harvard College. In 1875 he was invited to the U. S. Naval Observatory to use their 26-inch refracting telescope, the world’s largest at the time.

“Given what telescopes are today, can you imagine what he could have done with something that powerful?” Satrum remarks. “But for him to be able to come up with the details he did using what was available at the time makes his creations all the more astounding.”

Satrum emphasizes, “Trouvelot was very meticulous in getting accurate images. If you compare his work to what you can see through the Hubble telescope you’ll see they’re identical. He matched up perfectly the grid on the telescope to the paper he was drawing on; he represented exactly what he was seeing.”

Shortly after that, he went public, exhibiting several astronomical pastels at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. Because the exhibit was a big success, he decided to team up with New York publishers Charles Scribner’s Sons to publish a portfolio of his best drawings. In 1882, 15 of his drawings were made into lithographs.

While an estimated 300 of Trouvelot’s portfolios may have been published, only a handful of complete sets still exist. Initially, the collections were sold to astronomy libraries and observatories as reference tools that astronomers could use to compare with their own observations.

However, as early 20th century advances in photographic technology allowed for more accurate and detailed depictions of the stars, planets, and phenomena, these prints were discarded outright or sold to collectors.

According to Satrum, Trouvelot’s legacy is not without controversy. Born in Aisne, France, he fled to the United States in 1855 with his wife and two children following Napoleon’s coup three years earlier, settling in Medford, Massachusetts. While supporting his wife as an artist, he spent much of his free time studying insects, working to see if better silk-producing caterpillars could thrive in the United States.

During a trip back to France in the late 1860s, he collected live specimens of the gypsy moth, bringing them home to Medford. “Unfortunately, after hatching, some of them escaped his backyard, infesting the nearby woods, then quickly spreading throughout New England and Canada, destroying millions of hardwood trees,” relates Satrum.

Though large scale efforts to eradicate it were underway by 1890, they proved unsuccessful; the gypsy moth continue to be a scourge of U.S. and Canadian forests today, causing millions of dollars’ worth of damage annually. Satrum adds, “This episode also seems to have soured Trouvelot’s passion for entomology and by 1870 he had turned to astronomy.”

The Huntington’s set of Trouvelot lithographs was acquired by Jay T. Last as part of his collection of graphic arts and social history. It is but a small fraction of 200,000 objects that focuses on American lithography and graphics. And that assemblage, in itself, is noteworthy.

Satrum explains, “Jay got captivated by vivid images on citrus box labels which he found in rummage and flea market sales. These crate labels weren’t meant for retail sales but were primarily for middlemen and he wondered why these stunning images weren’t used as marketing tools to the general public. That led to his fascination, in the 1970s, with commercial lithography and advertising illustration, and other major reproductions of promotional artwork.”

“Jay donated his collection to The Huntington in 2005 but because he continues to acquire various objects we’re getting them in stages, which also makes it easier for us to process,” continues Satrum. “We have everything from tiny 3 x 5 business cards to master prints three times the size of these pieces.

The Trouvelot collection is a full portfolio set which we estimate to have a print run of 300 at a $125 apiece, which was a lot, considering that at the time they might have sold for between $4 and $6. Actually having a full set is really rare; most collectors have part of a set, or only the manual to accompany the set.”

“Having the manual makes the collection quite interesting because it reveals to us the beliefs at the time,” Satrum adds. “For instance, it shows the Milky Way and explains why you can see it at certain times. Trouvelot talks about Mars which has a bluish shade that he thought were oceans. Today we know that’s incorrect, but it was a reasonable hypothesis then.

I find particularly fascinating that they capture a moment in time. This is what research in Astronomy was in the 1870s and 1880s. That’s exactly what Mars looked like to him and scientists were able to match these drawings to what they observe through the telescope.”

“It also revealed how artists used this medium as an inexpensive method to reproduce their work. It was the best way to show what the original drawing looked like. Trouvelot wasn’t a lithographer, but we knew he supervised the process. We also know that the original of these illustrations were pastel drawings although I don’t know if he used any other medium,” Satrum states.

According to Satrum she has no underlying message or theme, “It’s a very visual exhibition and it’s specific in scope. We’re showing these 15 illustrations, not presenting a broader picture of Trouvelot, the artist. I simply want to share with our public a little bit about astronomy, and that these were originally drawings that were turned into lithographs. I put little comments underneath but I don’t intend to tell them what they should be seeing. I want people to take away from it whatever they want to take away from it.”

After the exhibition the collection will go back in storage and will be available for researchers to use. But until then we can marvel at Trouvelot’s collection of rare 19th century astronomical prints. Indeed entomology’s loss was the arts’ and astronomy’s gain, for his works capture the most breathtaking moments in time.