By May S. Ruiz

Southern California played a pivotal role in our country’s aerospace program when in 1936 the first rocket tests took place in Pasadena’s Arroyo Seco and launched the Rocket Age. Interestingly, the progress in the aeronautics industry in the region paralleled the growth of the science fiction community.

The Pasadena Museum of History (PMH) shows how science, fiction, and Southern California converge in an exhibition called ‘Dreaming the Universe.’ On view from March 3 through September 2, 2018, it explores the history of science fiction from 1930 to 1980, and its significance in the advances of science, the changes in technology, and shifts in American society.

Nick Smith, president of the Los Angeles Science Fantasy Society, curated this show that features historic artifacts, fine and graphic art, books and ephemera, and historic photographs. It will touch on the contributions of Ray Bradbury, Octavia Butler and other luminaries whose names are synonymous with science fiction; it will likewise highlight the fans and followers of the genre. Children and adults alike will find something they will instantly recognize as what initially pulled them into this exciting world.

Smith’s fascination with science fiction began several decades back. He relates, “Ever since I could read I read the ‘Superman’ comics. My barber would let us read whatever books he had, like ‘Incredible Hulk’ and ‘Super Spy,’ whenever we behaved. But the local library provided me the opportunity to read science fiction books written for younger readers. The earliest one I could remember was called ‘Have Space Suit Will Travel,’ about a kid who won a space suit in a contest and got caught up with things like aliens and other weird things.

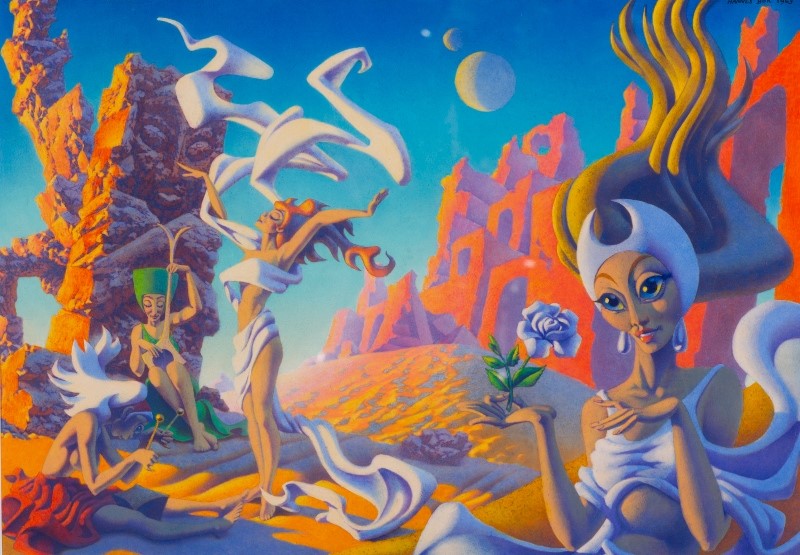

“Once I had an allowance and had the ability to buy magazines at the newsstand I started purchasing them. That actually influenced some of the artwork we have in this exhibition. I was at a magazine stand and my eye caught this really curious-looking wrap-around cover of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. It turned out to be a Hannes Bok illustration called ‘A Rose for Ecclesiastes.’”

“There were a lot of books and magazines about science fiction, fantasy, and speculative adventure written for kids in the 1950s and 1960s,” continues Smith. “They piqued children’s imagination because they were about the things that you didn’t see every day but would be fun if they did happen. They were wish-fulfillment fantasy to a great extent – traveling to Mars, or becoming space cadets to solve crime throughout the galaxy. That led to a lot of radio, television, and comic book science fiction.

“For adults, some science fiction dealt with warnings against abuses of technology which was what the original Frankenstein books were about, if you think about it. That was the first modern science fiction story written and it’s 200 years old now.”

“Laura Verlaque, PMH’s Director of Collections, and I worked for about a year identifying which things we would like to include in the exhibit that would be representative of the different aspects of science fiction. These items include visuals like flat pieces of artwork ranging from photographs to paintings; costumes – pieces of it or the entire outfit; physical objects from toys to window displays, especially in the 1950s.

“And that’s an interesting bit of the story. In the 1950s when Walt Disney put scientists on TV to talk about the space program, science fiction was all over radio and television. It was very much part of the culture in more ways than people didn’t think of. In fact, there was a company in South Pasadena that made window displays for jewelry stores and many of these had science fiction themes.”

“We don’t think about it nowadays but if we were to look back, science fiction was part of children’s experiences growing up,” points out Smith. “Tom Corbett’s ‘Space Cadet,’ which was very loosely based on science fiction story, was part of my background as a child. I watched that on TV, convinced my parents to buy me the little toys that went with it. A modern musician who, coincidentally, is named Tom Corbett uses a replica of the Tom Corbett lunchboxes at his concerts because he thinks it’s cool that a 1950s show had a character with his name.”

Science fiction’s integration into the mainstream culture took place in stages, says Smith. “There were some anthology science fiction shows on radio and television. ‘Space Patrol’ started here in LA as a radio show before it became a national television show and because they had big sponsors, they were able to get major publicity – they had a national giveaway of a backyard rocket ship clubhouse.

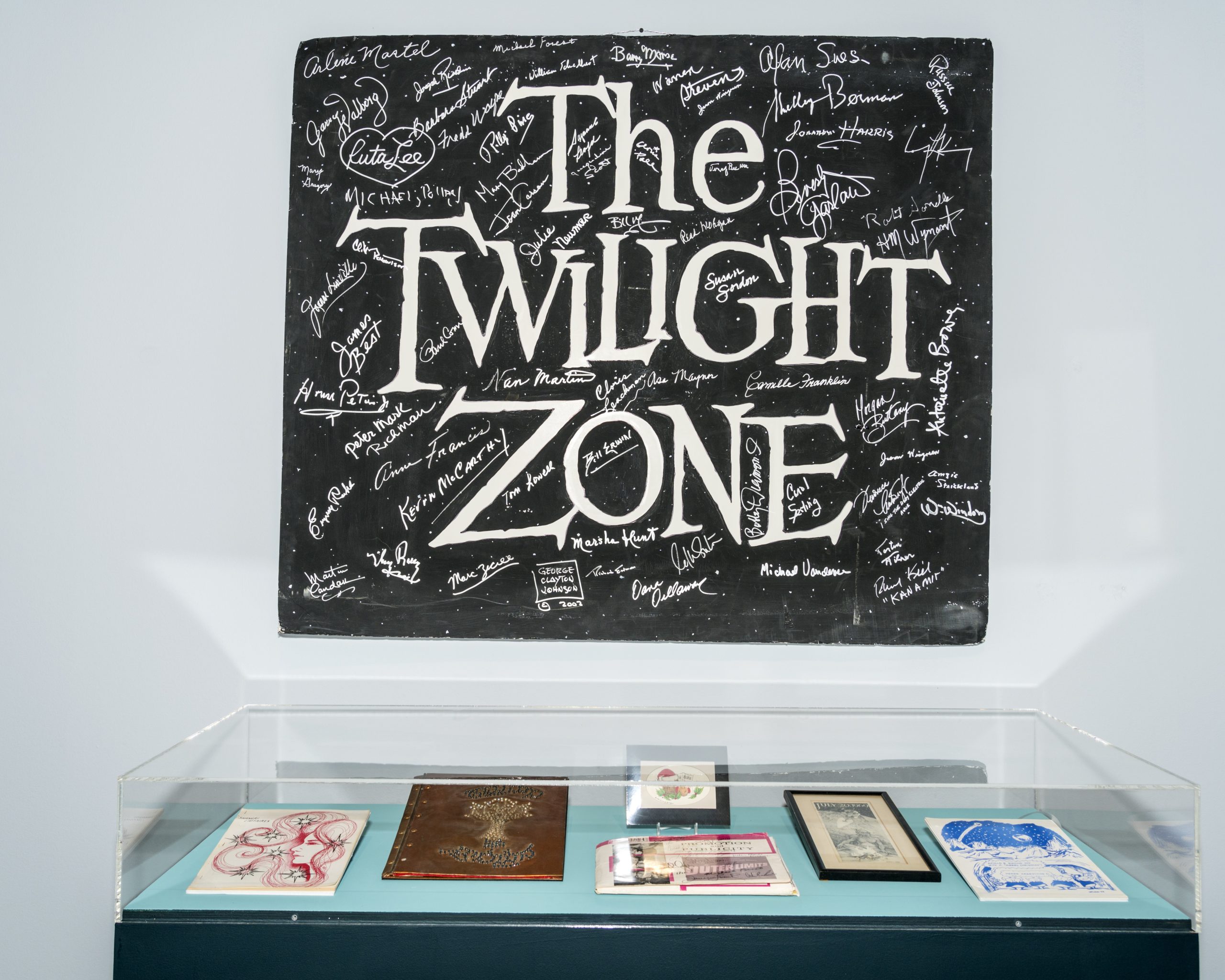

“‘The Twilight Zone’ came out in the 1960s but it was Star Trek that brought in the new wave of fans. It was hugely popular that when NBC cancelled the show Caltech students organized a march to protest it and they were joined by other enthusiasts and students from several universities.

“Here’s another curious thing – the genre attracted not just males. In this exhibit we have one of the earliest published science fiction female writers. Clare Winger Harris was born in the 1890s and wrote stories for two of the major sci-fi and fantasy magazines back in the 1920s. What makes her particularly noteworthy is that she wrote under her own name, not a pseudonym, at a time when it wasn’t socially acceptable and women didn’t think they could sell a science fiction story. There were no other women in the 1920s in science fiction magazines.

“A more recent famed writer Octavia Butler, who was Pasadenan, was remarkable because she was both a woman and African American. And at that point she was the most successful female African American science fiction writer.”

Adds Smith, “To a great extent science fiction is based in Southern California because the technology and the sources of technology are here, as well as the TV and film industry. Rod Serling didn’t have to travel very far to find writers to work on ‘The Twilight Zone.’ He was able to get some of the best scriptwriters by driving down the street. One such brilliant writer, Charles Beaumont, turned out amazing stories throughout the 50s and 60s. He’s largely forgotten now because he died fairly young but several of his stories became television episodes for ‘The Twilight Zone’ and ‘Night Gallery.’”

“Everything in the field of science fiction is being considered for television right now,” declares Smith. “There have been successful series like ‘Game of Thrones’ which are radically different from previous fantasy science fiction but they attract an audience which has never read the books they’re based on. The field is growing in several ways. However, not every project that’s started is shown because the genre deals with such big ideas that are difficult to realize.”

The books Smith read as a youngster were published by Erle Korshak. The distinctive wrap-around cover of the magazine that stopped him in his tracks at the newsstand is one of six graphic art on display in the exhibit from the Korshak Collection. This is the first time these artwork are being exhibited on the West Coast.

Stephen Korshak, himself, began his interest in science fiction illustrations when he was a child. He recounts, “My father owned a pioneering science fiction book company, Shasta Publishers, which ushered in the transition of important science fiction literature from magazines printed in cheap pulp paper to hardcover, library-quality books. These covers, which I was exposed to growing up, engendered my lifelong love for collecting science fiction art.”

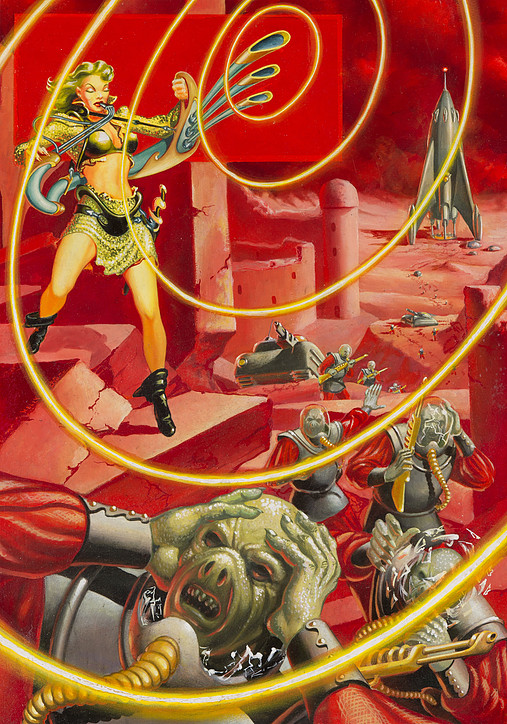

There are currently 90 pieces in his collection, with 29 pioneering American artists representing 80 years of published science fiction and 20 European artists from 15 countries who worked from 1863 to 1984. They can be seen online in ‘Korshak Collection: Illustrations of Imagination Literature.’ In the introduction he names one particular piece that stands out in his memory, “The J. Allen St. John illustration for the 1941 ‘Amazing Stories’ magazine cover of John Carter battling the dead in ‘The City of Mummies’ lured me into a fantastic world that I never knew existed. I read and enjoyed the Edgar Rice Burroughs story behind the illustration but, for me, the illustration itself gave me a sense of wonder I had never previously experienced.”

It is the only science fiction collection that tours, conjectures Korshak. And that touring bit came about quite by accident. He discloses, “I took one of the paintings to a framer and he told me it needed to be restored. When it came back from the restorer, my framer told me it was the talk of the restorer’s workshop. He asked me if I had any more of these illustrations and I said ‘yes.’ He said he wanted to display them here in Orlando, where I live, at one of the museums where he’s a trustee. The attendance was so overwhelming and the reception so amazing that we started to do the tours.”

Since it began touring nine years ago, the Korshak collection has been shown in some of the most prestigious illustration museums in the United States – the Brandywine River, the Chazen, and the Society of Illustrators’ – and at Museu Valencia in Spain.

“In the beginning, people were just tossing these illustrations away like the comic books because they weren’t worth anything,” says Korshak. “No one considered them to be art because artists were not supposed to be entrepreneurs – they were meant to work for the Medicis and have great rich patrons who would support their art. However, in the United States, it being a capitalist society, artists were businesspersons like everyone else. Illustrators, by and large, were educated, and had a family to support. They did it to make a living, to sell products and market books.

“For a long time there was a prejudice in the art world; the gurus and fine arts critics pronounced illustration wasn’t art. But there has been a reassessment taking place in the last 15 years or so; there is now a better appreciation for this art form. People paid $30M for a Normal Rockwell, who was an illustrator for the Saturday Evening Post. Maxfield Parrish, N. C. Wyeth, or Howard Pyle pieces go for millions of dollars.”

In the process of collecting, Korshak learned that illustration covers a wide field. He explains, “My love has always centered on a sense of wonder, that sense of being in a fantasy world, which I tried to capture with my collection. Except for a rare one or two, they are illustrations of literature spanning 125 years, from 1875 to 2000. There are thousands of illustrators and I can’t possibly display thousands of paintings. So what I tried to do was to pick what I thought, in my humble opinion, were the greatest illustrators or those who weren’t as technically famous but had a great influence. But we are not the definitive criterion of who’s great and who isn’t.”

Like a doting father, Korshak demurs when asked to pick the one he likes most, “It’s hard to say which is my absolute favorite but I’ll tell you three of my favorites. Jose Segrelles, a Spanish illustrator, is technically one of the eminent artists in the whole field but was little known in the United States. He made his name in Spain, although he did appear for a short time in the Illustrated London News. He appeared in books and magazines for 80 years but has been forgotten for the most part.

“I was lucky enough to go to Spain to meet his family. I bought the painting from his nephew and before he died I promised them I would take Segrelles back with me and introduce him to the American market. In fact, I will be collaborating on a book about Segrelles with Guillermo del Toro, the academy-award winning director, who said Segrelles was one of the great influencers in his life.

“Another illustrator who is highly esteemed by the cognoscenti is Arthur Rackham. He is a British illustrator who did magnificent work for children’s gift books, including Lewis Carroll’s ‘Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.’

“A third one would be Hannes Bok who illustrated for Weird Tales. These three illustrators, I think, are the best in their field,” proclaims Korshak.

Having this collection has afforded Korshak opportunities he cherishes, “There’s a camaraderie when you meet with other collectors. It’s a hobby you can share with other people which is tremendously fun and enriching. I have developed friendships through this.

“At the same time I really want to share and give back to the field that’s given me so much. The illustrators in my collection established the basic genre, the vocabulary of the field. These books haven’t appeared in print in 80 or 100 years, and out of sight out of mind. Many of the themes are reproduced by modern illustrators but in different ways and techniques.

“By exhibiting the artwork, I feel I’m doing something thoughtful by introducing these illustrators to a new generation of people and helping preserve some of these illustrators’ legacy as well. I’m not single-handedly going to do that but, in my own little way, am contributing towards that end.

“We’ve finished our East Coast tour and we’re now starting one on the West Coast. Coincidentally, I have just been contacted by a big gaming company in Japan that’s doing an Alice in Wonderland exhibition and wants to take one of our famous Arthur Rackham illustrations. It’s really exciting now that people are starting to know these illustrators. And I think it’s going to help the modern illustrators. My collection goes through 2000 but there are contemporary artists right now who are doing great work like Michael Whelan and the Brothers Hildebrandt.

“I have also written books on two illustrators – Hannes Bok and Frank R. Paul. I wrote the Hannes Bok book with Ray Bradbury before he passed away. It was Bradbury who introduced Bok to the editor of Weird Tales which helped start up his career.

“A few years ago I convinced my father to help me publish an artbook on the father of science fiction art, Frank R. Paul. We named the company Shasta/Phoenix because his original book publishing company, Shasta, had been inactive for 50 years and we resurrected it, like the phoenix, from the dead.

“In the Frank R. Paul book, I mentioned Sir Arthur C. Clarke, who co-wrote the screenplay for ‘2001: A Space Odyssey.’ Clarke claimed that Paul was one of the great influencers in his life. He said that the NASA space engineers who worked on NASA projects knew we could go to the moon because Frank R. Paul had visualized it,” confides Korshak.

If the people responsible for America’s space program look to science fiction books to determine which galaxies to explore, do we need further evidence that whatever the mind can imagine is humanly possible?