Larry Walls retired as LA deputy district attorney after almost three decades of service. After a very active professional life, he sat down to remember his “primitive years in Duarte that developed my character and personality.” His fascinating autobiography, Hurdles: Struggles of a Blackman in the Land of Milk and Honey, was recently released. On January 13, 2018, the Duarte Historical Museum will welcome Larry Dean Walls for a special presentation and reception at 4 pm. at 777 Encanto Parkway.

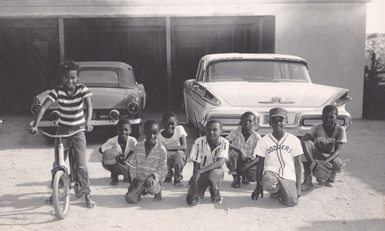

The Walls were a 1950s Black family in Duarte’s segregated Rocktown, near the quarry at the junction of today’s 210 and 605 freeways. Some of his neighbors included the Lees, Ross, Bullocks, Burnetts, Hardleys, and Shaws. In Hurdles, Larry depicts Rocktown or Durock as a place where boys looked to fight or, in Larry’s case, avoid fights the minute they left their front door. Athleticism in boys was strongly valued. Born in 1947, Larry said, “I had spinal meningitis at three and was physically challenged as a boy. I didn’t even get chosen to play Little League. I learned to adapt. I’ve never accepted inferiority but I don’t know ‘why me?’.”

While at Andres Duarte Elementary, a racially mixed school, Larry’s quick memorization of the multiplication table caused the teacher to accuse him of cheating, until he passed the test again at the principal’s office. He noticed all the Rocktown kids got less trick or treat candy than their White counterparts. In his first year at Duarte High, Larry got kicked off the football and track teams for no apparent reason. But he adapted to all. Larry learned to focus on what he could do, “I have a very good memory so Nell Painter, my Sunday school teacher at First Baptist Church, would have me recite all these verses and stories. I liked reciting. When we were boys, my friend, Roy Hayes, said to me once, ‘You’re intelligent. You’re an intellectual. You can grow up to be a lawyer.’ At the time, I only knew one Black man – Hardy Lee – who even owned a business. Mr. Lee painted cans for plant nurseries. How could I become a lawyer?” But the seed was planted.

Walls’ story is typical and atypical. His White great great grandfather, John Walls, left land for his slave children in Texas. Larry’s father, Dock Walls, was not encouraged to get more than a third-grade education as he already “knew how to count the pigs and cows on his ranch” in Northeast Texas. It was the family of Larry’s mother, Annie Bell Horton, that did not own land and valued education. The Hortons came to California with the Great Migration, in hopes of distancing themselves from the Jim Crow South. The families began as field workers in the cotton and raisin fields in the Fresno area. When mechanized farming took over Fresno by the mid-1950s, “Dad moved his growing family to Duarte to work on the San Bernardino freeway.”

Duarte and Monrovia’s African American history began in the 1870s when Lucky Baldwin recruited skilled workers on his Arcadia ranch. Some of these Blacks purchased land in Monrovia and some in Duarte for their families. Pasadena, Monrovia, and Duarte were the only San Gabriel Valley towns with significant African American populations. By the 1920s, racial segregation became common. Jobs in war industries and then in construction – and for the women, as maids – encouraged the ongoing westward migration of Black families. Both the Monrovia and Duarte African American communities would continue to grow into the 1970s. By 1980, African Americans constituted 9% of Duarte. Today, about 5% of the city is identified as African American.

In 1958, father Dock Walls was almost killed in a cave-in at his construction job; he suffered severed migraines for the rest of his life. Larry’s mother kept the family of ten together as a cook’s helper at the Old Kentucky Home restaurant and with welfare. The Walls then received a $5000 workers compensation check. In 1959, Kitty Kelly, a White real estate agent, sold them a home at 2122 Goodall Avenue. The Walls moved into an all-White neighborhood in the Maxwell area. In Hurdles, Larry writes, “Interestingly, shortly after we moved in, the Whites moved out. I saw For Sale signs go up immediately.” Within two years, Goodall became an African American community and referred to by some as “Little Africa.” The Goodall Boys gained quite a reputation too.

In high school by 1961, Larry was one of few African American boys on sports teams. To play sports, students had to maintain a C average. Larry writes, “in elementary schools, the majority of the best athletes were Blacks. Why not here at high school?… The Black students at Andres Duarte were having contests to see who could get the most F’s. Now it was telling on them at the ‘black hole,’ Duarte High School. This was the social design as perpetuated by the educational system. Sadly, the children and parents of Rocktown fell into this trap.” Many great young athletes from Rocktown were forced out of school. Larry remembers, “The school only had 87 Black students out of 1000, and only 10 were seniors.”

By 1965, there were race riots at Duarte High School. Larry writes about April in 1966, “All hell broke loose. Police and young people came from everywhere. The people were shouting and throwing rocks… To us, we were fighting racism in America… There were over 300 people and police officers from Monrovia, Temple City, Arcadia, and Azusa… The rioters attacked motorists and set buildings on fire… I loved it and was the right in the thick of it, yelling and screaming…”

Walls was arrested in this melee for “inciting a crowd to riot”. At eighteen, he told the judge in Monrovia he would represent himself at the jury trial as “I had merely exercised my constitutional right of freedom of speech.” Walls writes, “I had been watching Perry Mason, the trial lawyer show. Plus, the nighttime soap opera, Peyton Place.” And Larry was a member of the Duarte NAACP.

The jury found Walls guilty and the judge jumped in with, “You are a gang leader, a rebel rouser, trouble maker, and rioter. I will put you in jail as an example for all the other hoodlums to see.” Larry said he went into a state of shock and saw his future going down the drain. He did recover quick enough to become very humble and beg for probation. He also vowed right then and there to become a lawyer.

Larry Walls didn’t know you had to register to attend Mt. SAC; he did it in time. This Duarte boy went on to San Jose State as an athlete scholar where he was involved with Dr. Harry Edwards (1968 Olympic Boycott), Omega Psi Phi (historic Black fraternity), and the Black Power movement. He graduated from San Jose State in 1970 and Hastings Law School in 1974.

Some other Rocktown Boys are solid citizens and/or community leaders. Other Rocktown Boys ended up jailed, dead, or drugged. Many left Durock when they could. In fact, Rocktown is nearly forgotten. Larry Walls left Duarte but he carried his history as a “badge of courage.” He said, “I physically survived Duarte and I intellectually surpassed the institutionalized and individualized racism that was in Duarte.” We welcome him back to tell the story that is our community history.