When Jesse Hazelip showed up to his first New York solo exhibition in January of 2014, he did so with no hair or eyebrows. Freshly tattooed, he sat constrained in a plexi-glass cell for the entirety of the opening: speaking to no attendees, accepting no hugs and participating in no outside interaction.

Hazelip’s NY exhibition was nearly two years ago to the date, and since then, his passion and intensity for critiquing America’s post-Reagan era prison industrial complex has only become more imperative:

In October of 2013, the United States held the highest incarceration rate in the world, with 716 incarcerated individuals for every 100,000; in 2014, 6% of all black males ages 30 to 39 were in prison, compared to 2% of Hispanic and 1% of white males in the same age group; and while the U.S. represents roughly 5 percent of the world’s population, it’s somehow managed to currently house nearly a quarter of the world’s prison population.

For Hazelip’s latest exhibition “Don’t Shoot,” he will use his skill in visual arts, as well as his body, to reflect on those caught in the crosshairs of what many agree to be an unscrupulous justice system at best.

Jesse, you’ve been working with the on-going focus of the prison industrial complex for a couple of years now. Can you tell me a little about your past shows surrounding the topic?

My first show where the focus was on the prison industrial complex was at Jonathan Levine Gallery in Manhattan. For that show, I had a full body of work about the system. I did an installation where I built a 6 ft. x 9ft. plexi-glass cell, replicating the same size as solitary confinement. I was confined in there with a friend for the whole opening; we didn’t interact with the crowd at all.

At the same time, my best friend – who is in prison – was in the same size cell with another person for 23 hours a day. I was trying to mirror what my friend was going through and the conditions, so that people could get a diagram of it in person.

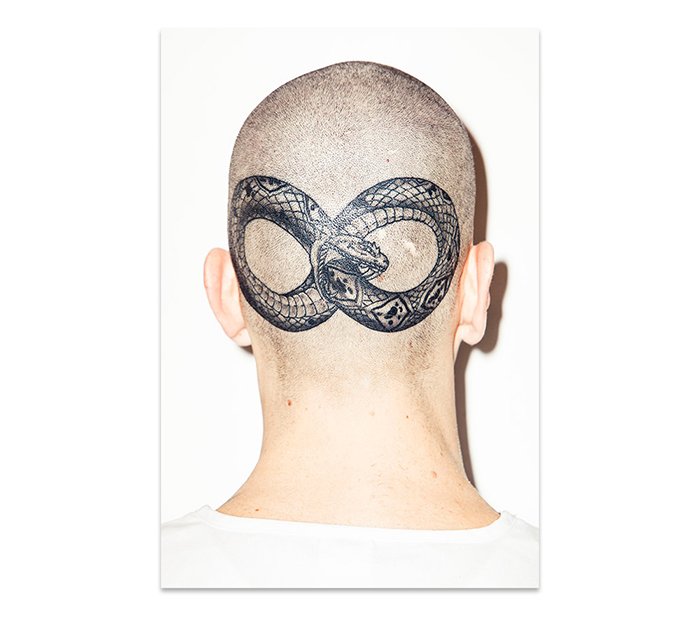

That show was called “Love Locks: Cycle of Violence.” Love Locks is the name of a prison, and I was representing the cycle of violence with the Ouroboros [an ancient symbol of Egyptian and Indian origins, which depicts a snake or serpent consuming its own tail]. I got the Ouroboros tattooed on the back of my head, and then I had “Love Locks” tattooed on my eyebrows for this exhibition as well.

Those tattoos were done prior to the opening of the show?

Yeah. I got those tattoos done ahead of time. At that time, I hadn’t considered doing a live tattoo.

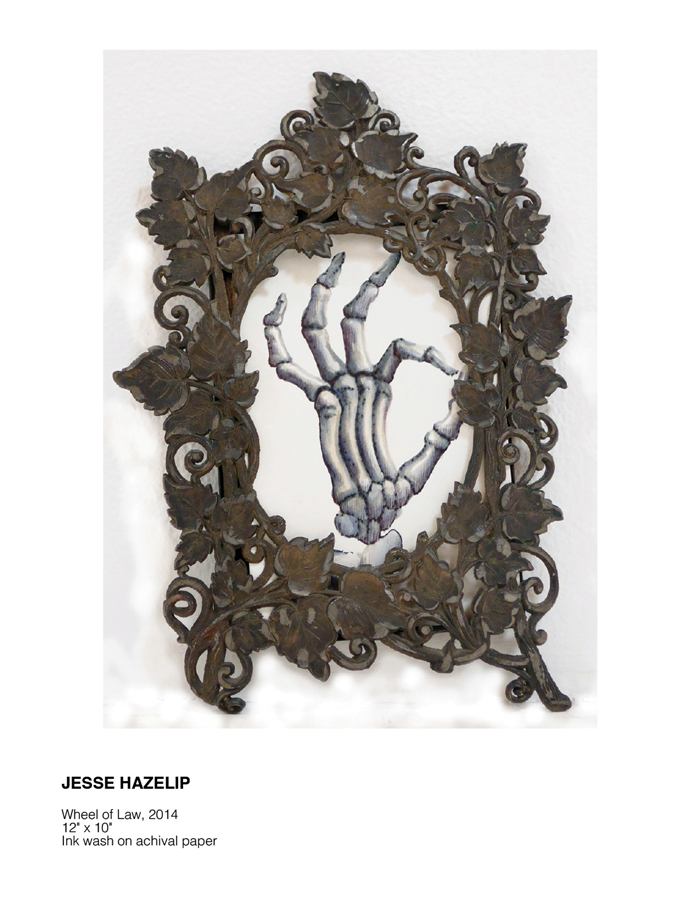

But the following solo show was Mark of Cain at Known Gallery. I built another representation of a solitary cell and I had the “Mark of Cain” tattooed on my temple during the opening. That show was an extension of new work made about the prison system as well.

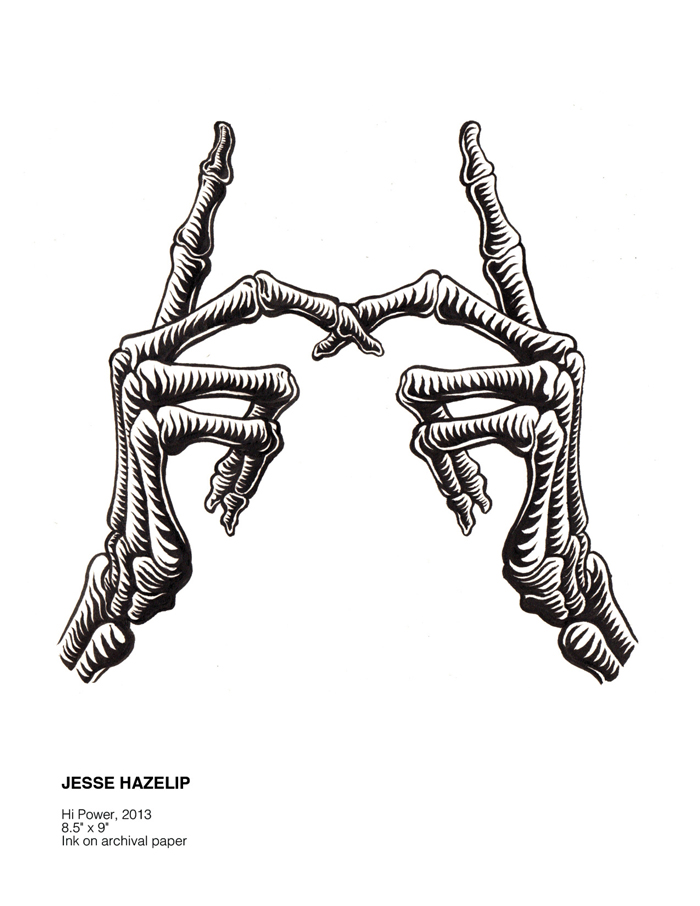

For Don’t Shoot, you’re having your palms tattooed with the aforementioned phrase. Can you talk about the decision to get the phrase tattooed on your hands?

I’d been getting extremely frustrated beyond words with all of the rampant police murders that don’t seem to be stopping or don’t seem to be taken seriously in regards to correction upon officers who abuse these rights. Any chance I have to use my platform, I want to address these issues. There’s so much evidence of people being murdered without cause.

So I decided I wanted to make a statement as soon as possible. I’ve actually been hustling to get this show together for quite a long time, but I had a lot of trouble finding a space that would allow me to do it because I think that my subject matter scares off a lot of people because it’s so abrasive and kind of straight to the point. I feel that most spaces don’t want to scare off money pretty much, but Mishka – right when I hit them up – they were like ‘yeah, we’ll do it, we’re down.”

And about the palms. . . I was initially going to get “Don’t Shoot” on the inside of my arms, but then a colleague of mine suggested the palms and that just made so much sense.

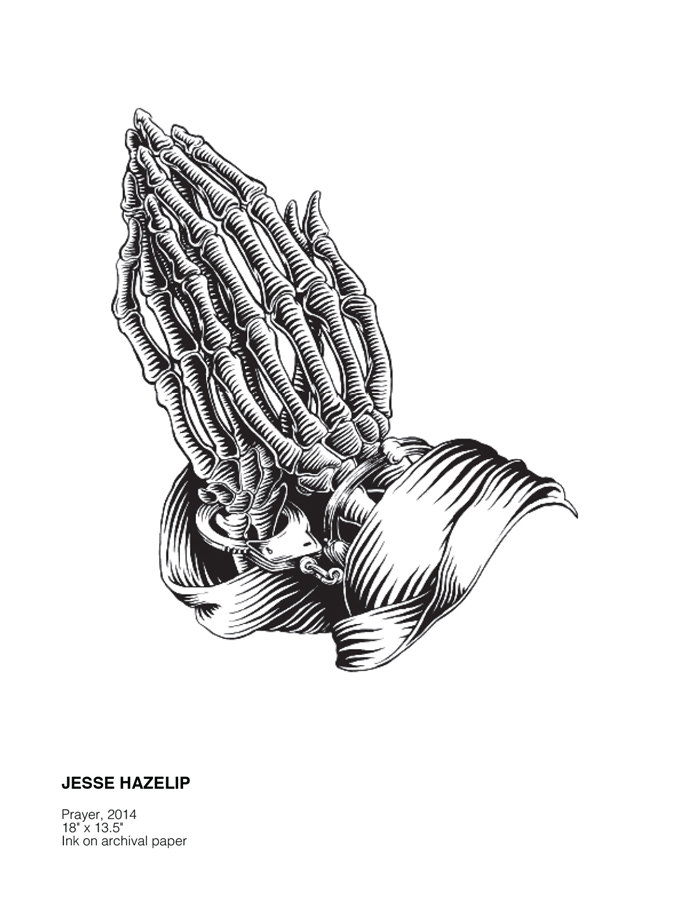

There’s religious connotation within the palms, but then there’s the stigmata and also palmistry—which is the reading of palms. On your palms, there’s the lifeline, and so there are all these [murdered] men, and I wonder what their life lines looked like. Their life lines have been stopped and it’s nothing that should be getting ignored, justified or swept under the rug.

“Don’t Shoot” is an easy directive to follow. Michael Brown’s case feels like the first to really gain media attention, which is sad because these murders haven’t started with Michael Brown. I want people to understand that this has been going on for an extremely long time. Don’t Shoot was birthed from Michael Brown’s death, and I’m doing it in honor of him and all these people affected.

How did you come about deciding to produce work surrounding the prison industrial complex? What’s the connection?

The idea to do work surrounding the prison industrial system first struck me when I was in county jail in San Francisco. I got arrested for graffiti.

I’ve been harassed by police since I was a teenager—maybe since I was like 13 – mainly because of the people I decided to hang out with or maybe the way I decided to dress; so I’ve known that there’s corruption, but I also knew from an early age that sure, I was getting harassed, but I wasn’t getting arrested.

It came to me at a certain point. A friend of mine pointed out, You know, you’re lucky you’re white.’ I was like, ‘what do you mean?’ He was like, ‘If that was me, I would have been in jail already.’

It took a while for that to sink in on me. Like, even though I was being harassed since I was a teenager, my skin color had kept me out of jail, and I think this is because police make a lot of racist assumptions.

When I did go through the system, I was very shocked by the treatment. I wasn’t expecting 4-star-hotel treatment, but the abuse of civil rights was extreme and very, very eye-opening. Throughout that process of going through County, I was just like, ‘this is ridiculous.’ It really got me to start considering making art about it.

When I got out, I was still in the middle of making work protesting the War in Afghanistan and Iraq, but then I started to dabble in making work about the system.

I was in County also at one point actually. The different ways in which incarceration affects millions of Americans is brushed over commonly— innocent people, children, friends. Can you talk about the ways in which incarceration effects larger groups within the country as a whole?

I think that most of America is living in a bubble; especially the white population. The general perception of our judicial system is that it’s just, and that individuals who work in the judicial system are doing their jobs correctly; they’re not considering that our judicial system has been corrupt since the days of slavery and the only things that have changed is the rhetoric, however.

I used to believe in our system. I used to believe in our country. I believed in what we preached; we preached that we’re the Land of the Free. I really tried my hardest to believe that, because I wanted to believe that we were the good guys. Everybody wants to believe that, but we’re lied to in our history books, and so it makes us look like the champions and the heroes. Also in our foreign policies we’re so judgmental of other countries, but we don’t stand up next to our own judgments. We’re a hypocritical system and I don’t think that people are aware of that hypocrisy.

The Jim Crow laws that were put into place after slavery were sickening, and they’re still in place, but the rhetoric has changed. I really encourage everyone to read The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander; that’s kind of been my bible as I’ve been researching throughout this whole process of talking about incarceration, mass incarceration and the racism involved.

The statistics don’t lie. People can choose to ignore it, but there are more people of color in prison than white people. Statistically, people of color don’t commit more crimes than white people, but they are incarcerated at a much higher rate.

There are around 2.5 million people incarcerated and all of those people have families; those families go to school with us, they work with us. 2.5 million is a massive amount of people, and that 2.5 million is only the number of people currently incarcerated. The number of people who are stuck in the system on house arrest for example, that’s like 5 million. That’s what “Mark of Cain was about; when you get marked as a criminal it’s really hard to escape it.

For Don’t Shoot, I’m going to be hanging work that deals with the focus of mass incarceration and the prison industrial complex. My really talented and awesome friend, Amer the Gamer of Lavish Tattoo in San Diego, is going to be doing the tattoo. He’s been in and out of jail himself and many of his friends have as well. There will be a memorial aspect to the performance of being tattooed also. I view it as kind of a sacrifice.

I was actually going to mention that next. Referencing the religious connotations and the act of now permanently altering your body, it does feel very sacrificial.

Yeah it really does. I actually never envisioned myself with head and face tattoos. Going into this, it was one of the most intimidating things I’ve ever done because I don’t necessarily look like someone who would typically get head and face tattoos. It really closed a lot of avenues for me [laughs]. But I really try and stay true to my visions, and when they come, I do my best to honor them. That doesn’t necessarily mean I’m happy about it though.

I was so scared going into that tattoo shop and shaving my entire head and eyebrows off and having no idea what I was going to come out looking like. What I came out looking like was the complete opposite than what I looked like the day before. It was very intimidating for me. I didn’t think about it at the time as sacrifice, but it came to me later that, ‘Yeah, I’m giving my body to this concept.’ It’s these extreme acts that I hope will trigger people to wake up and realize that [racism and incarceration] are very serious subject matters and that it does affect us all.

“Don’t Shoot” will hopefully bring more light to the severity of this. With the palms, it’s going to be extremely painful and there’s a thing with palm tattoos that all tattooers and people who get tattooed know; it’s really hard for the ink to get settled properly. I like that concept in itself because the tattoo is going to fade; it’s never going to completely go away, but it’s going to fade. I like that because I would like for this problem to fade.

Jesse Hazelip’s “Don’t Shoot” will open at Mishka’s LA flagship located at 128 S. La Brea on Friday, Jan. 8.